Remember when your law school career counselor told you that BigLaw was the only path to financial security and professional respect? Of course, that same counselor probably also said law review would be "fun" and that you'd "definitely use everything from Constitutional Law in practice." Some advice ages about as well as an opened bottle of milk left in a hot car.

For decades, bright-eyed law school graduates were funneled into large defense firms, convinced they had no choice—that prestigious work and decent pay required soul-crushing doc review marathons or playing the role of glorified paper-pusher in depositions. They stayed because they believed it was their only shot at building a respectable career while managing crushing student debt.

But the narrative that plaintiffs' firms can't compete is rapidly becoming outdated.

The Awakening

Several years ago, student groups like the Harvard Plaintiffs' Law Association (HPLA)—alongside counterparts at Stanford, Yale, and other top law schools—began highlighting an alternative path. These students sought careers that went beyond just landing any job; they wanted meaningful work aligned with their values, placing them on the “right side” of critical legal issues. As these groups gained traction, so did the National Plaintiffs' Law Association (NPLA), steadily dismantling outdated assumptions among peers who viewed joining a plaintiffs' firm with misplaced sympathy—as if it signified an inability to “cut it” in BigLaw.

This momentum accelerated dramatically over the past year as the legal community watched top BigLaw firms retreat into silence or submit in the face of Trump administration executive orders targeting prominent firms.

The Money Myth

Though more early-career lawyers are looking to the plaintiffs’ side, misconceptions persist. Many law students still believe pursuing plaintiffs' work means sacrificing significant income, assuming that doing good and doing well are mutually exclusive. Historically, plaintiffs' firm salaries were guarded like state secrets—probably because some firms paid embarrassingly low salaries while partners flew around in private jets.

Now, with pay transparency laws enacted in key legal markets such as New York, California, Illinois, and Washington D.C.—alongside a broader societal push for transparency—those secretive days are quickly fading. Some firms still drag their feet; as one named partner candidly told me, "We're transparent when it helps us." Apparently, "us" didn't include their associates, considering that the firm's first-year base hovers around $100,000 while certain partners... well, let's just say they're not worrying about student loan payments.

A San Diego-based firm took an even more defensive stance. We inquired about their publicly listed first-year salary of $115,000—another bottom-of-the-market figure. In response, they immediately removed the job posting. When pressed on the issue, they insisted they complied with all wage transparency laws yet kept their salary information private out of "respect" for their employees.

Methodology

We compiled first-year associate salary data from the most credible sources available, prioritizing firm websites, public job postings, reports from Vault, and direct communications with the firms themselves. Nearly all figures reflect 2025 salaries; for the one firm where current-year data was unavailable, we used its 2024 numbers (noted accordingly), supplemented by context from 2025 data for more senior associates. Here's the current landscape for starting salaries:

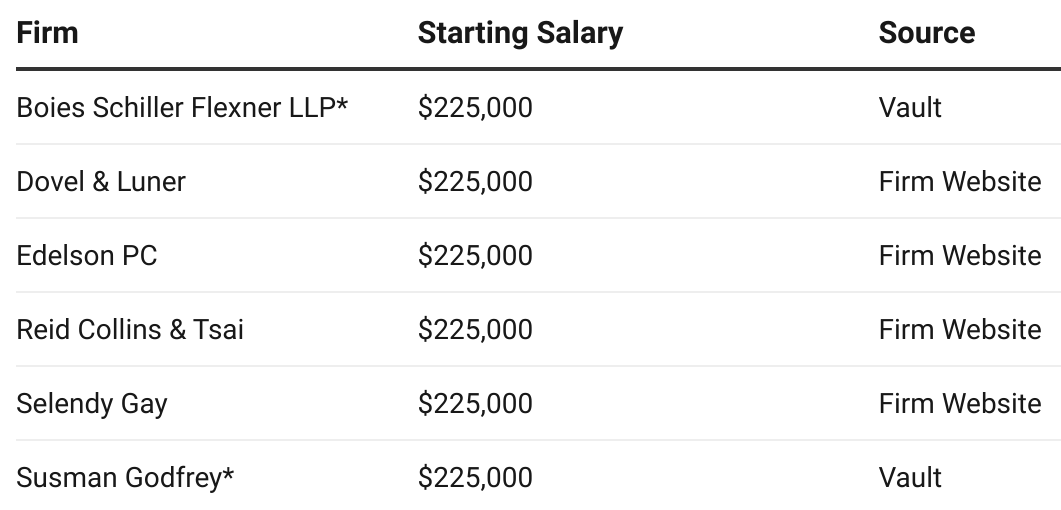

Tier 1: Matching the Top of the Market ($200,000+)

The most direct challenge to the old narrative comes from this growing group of firms. By matching or exceeding BigLaw first-year base pay (which tops out at $225,000), they signal an aggressive strategy to recruit top-tier talent, making it clear that lucrative, high-stakes work isn't confined to the defense side. Many firms in this tier also offer substantial bonuses, allowing them to easily outpace BigLaw’s total compensation.

Tier 2: Highly Competitive National Salaries ($150,000 - $200,000)

In this bracket, you'll find some of the top plaintiffs’ shops in the country offering highly competitive starting salaries. A base in this range represents formidable compensation in any major legal market.

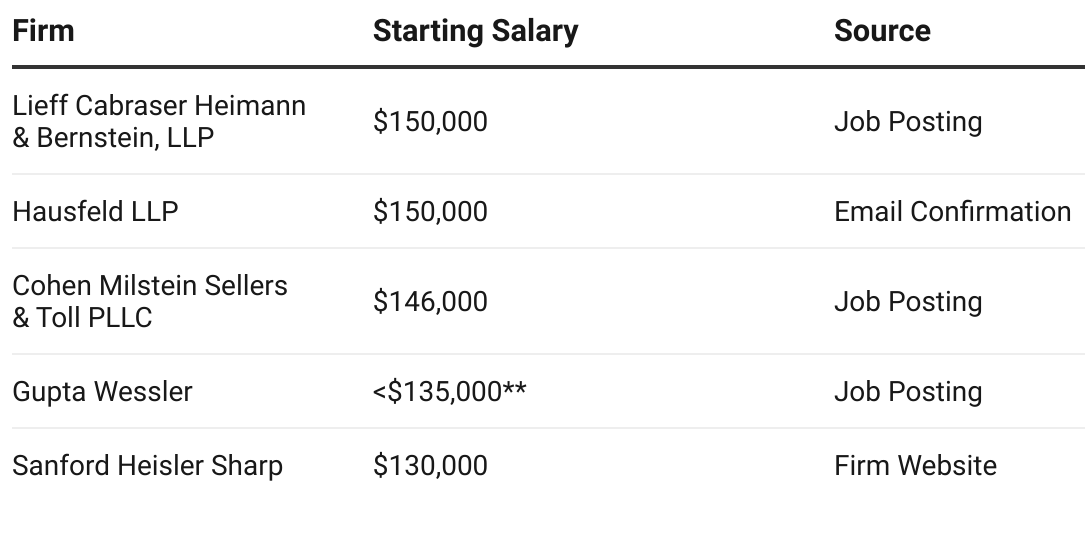

Tier 3: Falling Behind ($130,000 - $150,000)

This tier raises some eyebrows. While these firms enjoy national reputations, their first-year salaries remain notably low—especially given the enormous revenue their cases generate. Bonuses at many of these firms are reportedly disappointing as well.

Tier 4: Bringing Up the Rear (Below $130,000)

With firms on both sides of the “v.” setting 2025 first-year associate salaries at $225,000, a starting salary below $130,000 is difficult to justify for any firm competing for national talent. Some of the firms in this tier have compelling missions, but the basement-level starting salary is a stark reminder of the old stereotype that plaintiffs' work requires a significant financial sacrifice—an outdated narrative that other firms are actively dismantling.

* Boies Schiller and Susman Godfrey also handle significant defense work.

** Gupta Wessler is marked as "under $135,000" because only its second-year salary ($135,000) was publicly available. The firm did not respond to requests for first-year salary data.

*** DiCello Levitt disputes the $100,000 figure but declined to provide a specific alternative. Public job posting(s) for 2nd-5th years listed salaries at $110,000 - $150,000.

Big Picture

The compensation landscape at plaintiffs' firms is fragmented, spanning a wide spectrum. At the high end, elite firms view BigLaw's base salary as merely the starting point, adding bonuses that can leave defense-side paychecks far behind. Lower down, however, are firms that proudly tout billion-dollar courtroom victories yet quietly pay the associates who helped build those cases a fraction of their peers' salaries. The old rationale—that meaningful, mission-driven work necessarily demands financial sacrifice—rings especially hollow when associates witness outsized partner rewards generated from their own hard work.

Pay transparency, in the end, forces a reckoning for both firms and talent. As salary data emerges, attorneys can finally distinguish between firms truly aligning money with mission, and those merely asking associates to foot the bill for the victory party.

In an upcoming article, we will tackle some foundational questions: what drives the dramatic compensation differences across plaintiffs' firms, and what do those gaps tell us about how these firms operate? We'll also dive into senior associate compensation, where pay structures become much more complex and harder to decode.

What's Your Firm Paying?

Our compensation chart is a living document, and we need your help to expand it. If your firm is not on the list, or if you have insight into pay for senior associates and partners, we want to hear from you. Contribute in the comments or email us privately.

Next on Left Side of the V: A New Negotiation Series

We’re excited to launch The Backroom—a new series on how large-scale plaintiffs’ cases actually get negotiated. Not the polished version. The real one. Strategy, pressure, leverage, self-interest—and yes, even basic negotiating skill (or lack thereof)—all play their part, alongside quieter forces that shape decisions impacting legions of people and billions of dollars.

Jay, this is incredibly helpful. Thank you so much! As someone who hopes to work at a plaintiffs’ firm one day, this is gamechanging. I tried putting together something similar earlier this year and found it challenging, especially since so many firms don’t hire straight out of law school. Thought I’d add a few more data points I came across in case anyone else is curious, though I haven’t emailed or inquired with the firms to confirm:

Bredhoff and Kaiser: $156,000 (website)

Kline and Specter: $120,000 (job posting)

Kessler Topaz: $130,000 (job posting)

There are also boutiques like Kellogg Hansen and Hecker Fink that seem to match the top of the market, though like Boies, they do a fair amount of defense-side work.

One trend I noticed is that some plaintiffs’ firms are starting to require a one- to two-year internal clerkship or fellowship for new grads, usually paying around $90k–$110k before you move into an associate role. That seems to be the case at Cohen Milstein, Loevy and Loevy, and Tycko and Zavareei.

Following, especially if you ever open the curtain on mid-level associate, senior associate, and non-equity partner pay at said plaintiffs firms.